|

| The Douglas B-18, which had been designed to meet a US Army Air Corps requirement of 1934 for a high-performance medium bomber, was clearly not in the same league as the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, which had been built to the same specification. Figures highlight the facts: 350 B-18s were procured in total, by comparison with almost 13,000 B-17s. In an attempt to rectify the shortcomings of their DB-1 design, Douglas developed in 1938 an improved version and the proposal seemed sufficiently attractive for the US Army to award a contract for 38 of these aircraft under the designation B-23 and with the name Dragon.

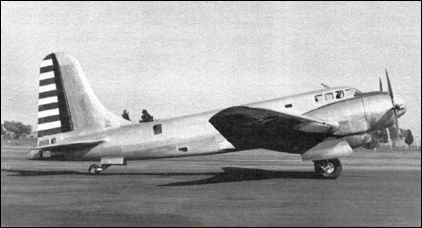

Although the overall configuration was similar to that of the earlier aircraft, when examined in detail it was seen to be virtually a new design. Wing span was increased, the fuselage was entirely different and of much improved aerodynamic form, and the tail unit had a much higher vertical fin and rudder. Landing gear was the same retractable tailwheel type, but the engine nacelles had been extended so that when the main units were lowered in flight they were faired by the nacelle extensions and created far less drag. Greatly improved performance was expected from these refinements, plus the provision of 60 per cent more power by the use of two Wright R-2600-3 Cyclone 14 engines. An innovation was the provision of a tail gun position, this being the first US bomber to introduce such a feature.

First flown on 27 July 1939, the B-23s were all delivered to the US Army during that year. Early evaluation had shown that performance and flight characteristics were disappointing. Furthermore, information received from the European theatre during 1940 made it clear that development would be unlikely to result in range, bombload and armament capabilities to compare with the bomber aircraft then in service with the combatant nations, or already beginning to emerge in the USA. As a result these aircraft saw only limited service in a patrol capacity along the US Pacific coastline before being relegated to training duties. During 1942 about 15 of these aircraft were converted to serve as utility transports under the designation UC-67, and some of the remainder were used for a variety of purposes including engine testbeds, glider towing experiments and weapons evaluation.

Following the end of World War II many surplus B-23s and UC-67s were acquired by civil operators for conversion as corporate aircraft. The majority were modified by Pan American's Engineering Department, equipped to accommodate a crew of two and passengers. Some of them remained in civil use for about 30 years.

| A three-view drawing (562 x 766) |

| MODEL | B-23 |

| CREW | 4-5 |

| ENGINE | 2 x Wright R-2600-3 Cyclone 14, 1193kW |

| WEIGHTS |

| Take-off weight | 14696 kg | 32399 lb |

| Empty weight | 8659 kg | 19090 lb |

| DIMENSIONS |

| Wingspan | 28.04 m | 92 ft 0 in |

| Length | 17.8 m | 58 ft 5 in |

| Height | 5.63 m | 18 ft 6 in |

| Wing area | 92.25 m2 | 992.97 sq ft |

| PERFORMANCE |

| Max. speed | 454 km/h | 282 mph |

| Cruise speed | 338 km/h | 210 mph |

| Ceiling | 9630 m | 31600 ft |

| Range | 2253 km | 1400 miles |

| ARMAMENT | 1 x 12.7mm + 3 x 7.62mm machine-guns, 2000kg of bombs |

| Anonymous, 13.03.2023 16:19 The B-23 was designed to succeed the Army Air Corps' Douglas B-18. However, by the time it appeared it was obvious to the Army Air Corps that the Boeing B-17 was the better choice for the heavy strategic bomber role while the Douglas A-20 was the better choice for the light tactical bomber role. reply | | Michael Meek, e-mail, 03.07.2017 01:24 I recall seeing the B-23 parked at Houston Hobby back in the late '60's-early '70's and someone then saying that it belonged to oil man Clint Murchison but, since an earlier poster mentioned "Curly" Korb and because it was on the old Houston Executive Air Service ramp, perhaps it was one of the varied fleet of Brown & Root? Also, rumored that this same airplane eventually became part of the CAF fleet. Maybe someone with better knowledge will chime in. reply | | Jim Evart, e-mail, 15.03.2017 10:08 My dad flew a converted B-23 for The Pacific Lumber Company based at Oakland airport. Shortly after he left PLC, the successor pilot crashed it in Akron, Ohio around 1952 during an instrument approach. It was totally destroyed with no fatalities. reply | | lee gordon, e-mail, 17.11.2016 03:43 what ever happened to the b-23 that sat in southeast corner of hobby airport in early 1960's ? sat next to former owner howard hughess 307 stratocruiser reply | |

| | Doug Leisy, e-mail, 19.09.2016 18:44 Re: Lee Korb's comments; I remember seeing your dad's B-23 at Allegheny County as a kid. My dad (Don Leisy) was a captain for Capital Airline flying out of there, and I remember him talking about "Curly" Korb and the B-23. Those were good days. reply | | michael, e-mail, 17.09.2014 19:26 what was the person name who invented this plane thanks for the info reply | | War Reese, e-mail, 25.12.2013 09:22 Does anyone have a list of movies that the B-23 has appeared in ? I have 4 movies that I've purchased with the B-23 in them . reply | | Lee Korb, e-mail, 16.11.2011 00:13 Great site! Lots of memories...

My father flew a B-23 for Westinghouse Elec. out of Allegheny County airport in Pgh.,Pa. Back in the late '50s. I think he was checked out by Al Uelchi who flew a B-23 for Juan Tripp while he was Pres. of Pan Am. Al was the founder of Flight Safety, and Dad was one of his early customers... reply | | dafag, 20.06.2011 14:12 At that time Jaun Trippe's personal aircraft was a B-23 and was hangared at LaGuardia.On occasions it was brought over to Idlewild for maintenance. reply | | Michael R. Nowicki, e-mail, 09.06.2011 16:57 I flew a B-23 in the mid 60's owned by Green Bay Packaging Corp. This A /C had been owned by John Deer Corp and Pan AM. Now sits at the Pima Air Museum in Tucson, Az. reply |

| Nick Oland, e-mail, 21.09.2010 21:36 I flew a B-23 for Lehman Brothers of New York City

to Texas and back in 1953 I was a corporate pilot in the

1950s through 1980s reply | | Connie Luhta, e-mail, 24.06.2010 03:42 A B-23 was based at my airport in the 70s. It was purchased by Kermit Weeks, then heavily damaged in Florida by Hurricane Andrew. I hope he is going to rebuild it. I have about 1200 spare parts in my attic that I hope to sell some day. reply | | Carl, e-mail, 07.02.2010 21:06 A Dragon, belonging to the University of Wash. was damaged in landing at Kingman AZ in the '80's. I got to go through it while there. In the movie Tucker, there is a short shot of a B-23 with mountains in the background. The B-23 clip was to portray Tucker's flight to the west coast to obtain engines for his cars. Those engines being Franklins (Air Cooled Motors). reply | | Eugene H, Secord, e-mail, 30.12.2009 20:01 In 1956 I went to work for Pan Americam World Airways at Idlewild.At that time Jaun Trippe's personal aircraft was a B-23 and was hangared at LaGuardia.On occasions it was brought over to Idlewild for maintenance. reply | |

| | SEO, e-mail, 02.05.2009 03:23 My father was in the aircraft business in the 1960's and at one point represented a businessman in buying a B-23 as a personal plane. We had a room in the basement full of spare B-23 parts for a while, all gone now.

One of the things I remember him saying was that some of the B-23's were fitted with a dummy extra pair of engines, and were used in filming "Twelve O'Clock High, I don't know if it was the movie or the TV show.

Does anyone know if he was right about that?

Thanks

Stephen Olson reply |

|

Do you have any comments?

|

|

COMPANY

PROFILE

All the World's Rotorcraft

|

Is this the same Mike Nowicki firm DuPage airport?

reply